Arkane’s Prey has created a world where I actually care about the choices I make.

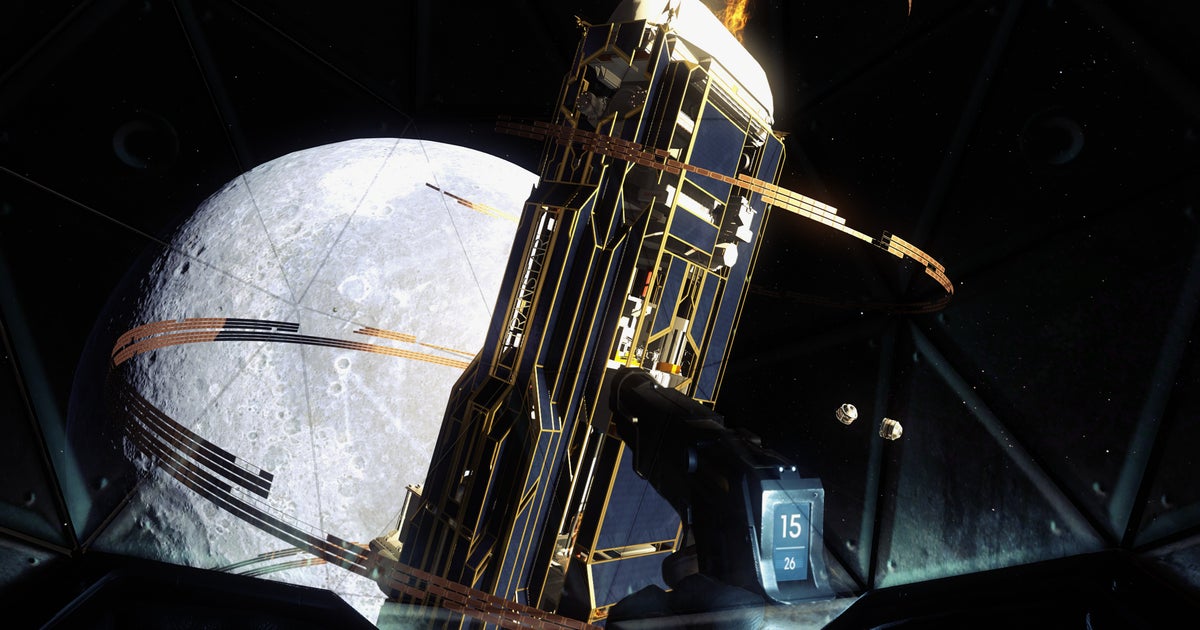

The future is lonely. Trust me, I’ve been there. Over the last few weeks I’ve been replaying Arkane Austin’s Prey, an immersive simulator where you explore a space station orbiting the moon. You’re trying to figure out what went wrong and why the whole place is overrun by hostile aliens. It’s an interesting tone though. Despite the nasty life on the space station, you spend a lot of time alone – and that doesn’t mean there’s no sense of humanity in the game.

Of course, for most of Prey’s playtime, interaction with other living people is a relative rarity, especially in the early hours, when anyone with a pulse you happen to encounter usually doesn’t stay that way for more than a few seconds. The advanced space station Talos 1, once considered a shining beacon of human genius and scientific progress, now serves as a de facto floating prison for everyone trapped on board, including protagonist and TranStar non-baby Morgan Yu. is an unfettered ultra-capitalist conglomerate dedicated to researching the alien creatures known as Typhon. Every sci-fi game needs. in such a company.)

Watch on YouTube

Because of this relative isolation, you learn more about the TranStar team (mostly made up of scientists and engineers) by poking through their private messages as if you were a nosy parent of a teenager. Not just personal messages, but also emails, journals, reports and other written ephemera. Of course, when Prey was released in 2017, the concept was hardly new. It’s practically a staple in the immersive simulation genre. What makes Prey special in this regard, however, is the way its writing breathes rich life into the characters before you even have the chance to meet them.

The TranStar team is more than just a collection of bodies used to demonstrate narrative moments or as interior environmental set pieces. They are people. For example, let’s look at Abigail “Abby” Foy and Danielle Shaw, the space station’s lead sanitary engineer and technical systems administrator, respectively. Abby and Danielle have to be in the top 3 on my list of romance plots in games, if not number one. Despite everything Prey likes to throw at you, from the evils of corporate greed to the endless human arrogance, the romance between two colleagues always brought a smile to my face whenever I came across their communication devices, known to the world as “transcribers.” language of the game. In one audio recording, titled “Dear Future Us,” Abby even describes their messages together as a form of “mental scrapbooking.” Together they “preserve important moments.”

Things like this give off a warm glow, even if we later find out that the relationship didn’t survive. All it took was one relatively light-hearted joke from Abby for Danielle to end things with a depressingly distant, “Go away, we’re done.”

I should have expected this. Prey is a game where the small positive moments shine brightly because they exist in contrast to the dark backdrop of space and its lonely horrors. And yet, ever the optimist, I hoped for a happy ending to Abby and Danielle’s story between aliens that terrified me by imitating every possible object, and hiding in plain sight by monstrous monsters known only as Nightmares, hunting me for sport. But as I dove and made my way through the main campaign, that hope began to fade. Danielle’s inevitable calls for someone to respond to Abby’s status practically echoed through the cold, empty halls of Talos I. And again: I should have expected this.

In any case, not everyone is in love. Luka Golubkin, another member of the Prey cast, is the epitome of a dark character. Facial scars that indicate he’s all too familiar with knife fights, combined with thick-framed glasses and an unfortunate hairline, make him almost look like the evil math teacher from an ’80s teen sitcom who got locked up for finally broke. After just a few seconds of conversation, I knew I could only trust him as much as I could. His aggression towards his robot assistant, the awkward… pauses in his speech when he talked about himself, the fact that he refused to offer Morgan refuge in his barricaded kitchen until he was given what he wanted? Clearly something was wrong. For someone who was giddily combing through every note and email I could find, his “chef” demeanor wasn’t all that convincing.

Without even noticing that his tone of voice and mannerisms were not the same as in the transcripts of the real chef Will Mitchell, I had simply watched too many horror films to believe that dealing with someone like Luca would end without a knife in my body . back. But since he (predictably) betrayed me and left me to die in the freezer, the only emotion I felt was pain. I realized that his previous victim was Abby. Hanging limply in a pool of her own frozen blood, she clutched the transcript, which contained a message from Danielle asking if she was okay and asking to meet her at the fitness center.

But the real kick in the gut was when I came face to face with Danielle after all this, when she realized that my presence meant Abby was gone. After all, that meant I got her message instead. In other words, there was no coming back from what was said – only the bitter hope that Abby could get revenge.

Real talk: At this point in the game, Daniel is floating into outer space outside of Talos. I’m trying my best to avoid the Typhon crisis. Slowly losing oxygen and her cognitive abilities beginning to weaken, she sends me one last message as I investigate: “One last thing. O2 is almost gone. (…) Don’t let him get away.” Jeepers.

It’s easy to forget that the entire storyline involving Abby, Danielle, and Luckin is optional. Your decisions here do not affect the ending of the plot – in fact, you can skip this branch altogether and complete the game without solving the story of the killer cook.

It’s exciting because immersive simulations are a playground for new gameplay and player choice. Prey shines brightest when it builds a world where you care about the decisions you make and the results they bring. You could give someone more choice than the stars in the sky, but if you’re not interested in the long-term effect, then what’s the point? I wanted To save the Talos I crew, the plot gives you that opportunity, but Morgan doesn’t seem to remember enough to care one way or the other. Even after I received what is considered the best ending, I couldn’t help but mourn the lives of those I couldn’t save.

Even though it wasn’t a huge commercial success, I was really hoping that Arkane would get another chance to make a sequel to Prey. I felt that the community sentiment was too strong and that its status as an underrated gem would one day lead to a continuation of this rich fantasy, and that we could learn more about the history of the Yu family, TranStar, and the ending had so many different branching possibilities. But after the unfortunate closure of Arkane Austin in 2024, the likelihood of that ever happening is unfortunately close to zero. Prey has an atmosphere and feeling that cannot be replicated. It was something truly special and I won’t forget it – not a word.